Henry Benjamin Herts, born in 1794, was living in England when he had his family. His children included, his daughter Rachel (b. 1819), and his sons Henry B. Jr. (born May 26, 1823 in Nottingham, died 1884), Daniel born about 1825, Jacob, and Lewis. They were all born in England.

In 1841 Henry Sr. opened a steel pen factory under the name H. B. Herts & Co, at 281 Bradford St. in Birmingham. According to Brian Jones’s book People, Pens & Production, the factory operated from 1841-1842.

In 1843, at age 49, Henry Sr. came to the United States and settled in New York. He created a partnership with his sons Henry Jr. and Jacob called H. B. Herts & Sons. They set up a factory at 509 Broome St. in New York City where they manufactured stationery (probably blank books), pen holders, and maybe pens.

The reason I say “maybe” is that while H.B. Herts & Sons is listed in various directories as a “manufacturer of metallic pens, penholders, stationery, &c” the advertisements promote the pens as being made in Birmingham. In a large ad in the Doggett’s directory of New York City for 1846-47, it explicitly says that the pens are made at the Bradford Works in Birmingham.

This wasn’t the first pen they started advertising. The first ads in 1845 mention the Alpha Pen.

In 1846 is when you first see the reference, above, to the amalgam pen you also find the claim “By Royal Letters Patent.” The only problem with this is that I cannot find a British (or American) patent that fits this pen. Perhaps someone else can find it, but it has eluded me. If you do find something you think works, let me know.

The Royal Letters Patent claim also shows up in an interesting ad in 1847. This ad claims that the Amalgamated Silver, Steel and Platina Pen was first introduced into the US in August, 1845 “at which time the manufacturers were unknown to the writing community; the pen, therefore, had to stand on its own merits.”

Because of the superior quality of the pens, they claim that between December 1845 and December 1846, they sold 375,000 gross, or 45,000,000 of their pens. It is in this ad, as well, that they refer to their business address as the “manufacturer’s depot” and list not just their NYC address, but also 35 Cornhill in Boston.

We can compare this 375,000 gross of pens Herts produced in 1845 with the 730,031 gross Gillott claimed to have made in 1843. Herts was no where near as large, but they were making quite a respectable number of pens nonetheless.

The family stayed pretty close, literally, through the years of the business. When the directories show both business and home addresses, Henry B. Sr. is shown as living with at least one, and often two or even three of his sons in the same house over the years.

There’s evidence that some of the sons made trips back to England in at least 1846 and 1849. It’s likely they kept the factory open in Birmingham and perhaps kept it running by other sons or relatives. Since we’ve not found evidence for the factory after Henry left in 1843, it’s not clear if they really still had their own factory, or just had pens stamped with their name by another maker, and just attributed them to their old Bradford Works.

Regardless, they kept selling the pens as H. B. Herts & Sons until 1853 when Henry B. Sr. retired and the old company dissolved. The new company, “Herts Brothers” continued to sell pens as well as import stationery and fancy goods in their new office at 241 Broadway.

An interesting ad/article in the March 2, 1854 Buffalo (NY) Morning Express gives us more information about the company. It talks about “Herts Brothers Amalgamated Iridium, Zinc and Platina Pens” and “The Messrs. Herts are at the head of the great house in Birmingham, England, for the manufacture of Metallic Pens. They employ about 500 persons in their extensive operations.” This pen is patented in England and the United States by ‘Herts Brothers.’ It is for sale at their splendid Emporium, 241 Broadway, as well as in different parts of the Union, England and France.” If they truly had 500 employees then they were quite a good sized company. The well-known D. Leonardt, one of the largest of the independent makers in Birmingham, had 500 employees at its height in the 1880-1890’s, and that included their own rolling steel operation.

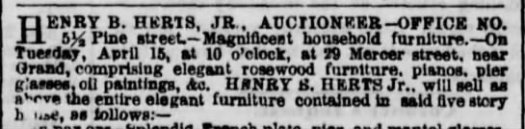

Alas, the “discerning public” did not flock to this pen, and in 1855, Herts Brothers was no longer listed. Jacob is still listed as a “stationer” but it does not tell us where, and Henry B. Jr. has set himself up in his own auction business.

Interestingly, Henry B. Senior just can’t stay away from family, or completely in retirement. In the 1855 New York Census we find Henry B. Herts Sr. living with his daughter Rachel and her husband Jacob Davis. Both Jacob and Henry are listed as at the same business address with Henry labeled “jeweler” and Jacob as a watchmaker.

Henry Sr. died about 1856. Henry Jr. lived until 1884 when he died on a trip to England at the age of 63. Many of his children went on to start up their own businesses including another Herts Brothers, this time Herts Brothers Furniture.

The history of Henry Benjamin Herts still has some mysteries to be solved. It seems from the advertisements that the Herts family may still have had a factory making pens in Birmingham. It’s not clear if all of their pens were imported from that factory, or if some were made in the US, or if they got some from other Birmingham factories, or some combination of the three. Further research on the Birmingham side may be done, but the standard resources don’t mention the Herts family or the Bradford Works beyond that brief mention in Jones’ book. If they were as big and prosperous as the claims, then their omission from the standard histories is a significant one.

We also still have the mysterious patent claims. I cannot find any record of patents claimed in England or the US. For now, it remains yet another mystery.

Harry B. Herts came to America as so many others did, and while his pens seem to have, at least partly if not completely, been made in England, he chose America as his main marketplace as well as home. Because of that, I still consider H. B. Herts & Sons as another of the interesting American pen makers of the 1840’s.